The Georgians, and the Regency period in particular, are

generally known for extravagance in all things – well, for the privileged few

who could afford it – and food was no exception. The court of the Prince Regent

(aka ‘Georgie-Porgy’, ‘Prinnie’ or ‘The Prince of Whales’ - don’t ever let

someone tell you people used to respect authority figures) was opulent and

indulgent, demanding the very best in spite of the occasional cash-flow

problem. The king kept his son on a short leash financially, by royal standards, but few people would refuse to lend to the Prince of Wales.

Anyway, as the younger George’s gluttony was famed, food was naturally a

priority.

On June 15th 1817, a dinner was served that included over a hundred courses. This was provided by the famous French chef Antonin Carême, possibly the best candidate for the first ‘celebrity’ chef. After the French Revolution at the end of the 18th Century, a lot of high-profile chefs who had previously been in service to the aristocracy were out of a job – so were available to work in other countries, bringing their styles and techniques with them. He was lured to Brighton Pavilion, the Prince’s holiday residence, but left after just a year despite the state-of-the-art kitchens; fed up with his patron’s gluttony. (The fact that a chef had a problem with this is an indicator of just how decadent that court was.)

On June 15th 1817, a dinner was served that included over a hundred courses. This was provided by the famous French chef Antonin Carême, possibly the best candidate for the first ‘celebrity’ chef. After the French Revolution at the end of the 18th Century, a lot of high-profile chefs who had previously been in service to the aristocracy were out of a job – so were available to work in other countries, bringing their styles and techniques with them. He was lured to Brighton Pavilion, the Prince’s holiday residence, but left after just a year despite the state-of-the-art kitchens; fed up with his patron’s gluttony. (The fact that a chef had a problem with this is an indicator of just how decadent that court was.)

Not everyone was wholehearted about the fashion for

intricate French dishes, however – many women cooks and writers (such as Hannah

Glasse and Elizabeth Raffald, discussed a couple of entries back) were

advocates for ‘plain English cooking’ and among wealthy men there was a group

who made a point of belonging to a high-profile dinner club: The ‘Sublime

Society of Beef-Steaks’, which revolved around dinners of enormous steaks,

baked potatoes, onions, port or porter to drink and the strict exclusion of

women. (Presumably this makes the meat tastier.)

Still, despite the occasional backlash, new flavours and

techniques characterised Georgian cooking, and with them came willingness to

experiment. The explosion of tea’s popularity was only one among several new

fashions – coffee also became stylish, and because it was harder to fake the

taste, stayed in heavy and expensive demand, particularly once coffee-houses

began appearing, centres for sociable discussion and intellectual thought (in

theory) across London and the larger English towns and cities. How things do

change.

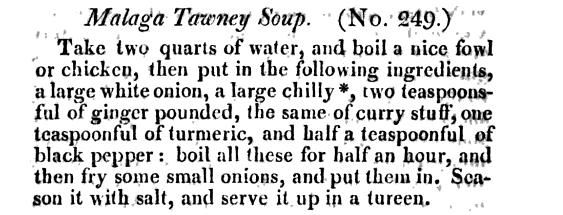

For today’s recipes, I wanted to try some things with less

usual tastes – for Georgians and for modern cooks – curry. Once I knew the

Georgians were using Indian flavours in their cooking, I knew I had to try and

find an authentic recipe – and the one I chose was ‘Malaga Tawney soup’ – the

original mulligatawny. Apparently, the English abroad were so concerned by

Indian food not featuring a soup course that this was adapted – missing the

point as unerringly as people still do when they go on holiday to foreign

climes and insist on a full English breakfast every morning.

This recipe is a simple one to make – particularly scaled

down for one person (as I made it – two quarts is equivalent to four pints, and

nobody needs that much soup unless they’re holding a party.) Here what I did:

1 chicken breast (all hail supermarket convenience)½ pint water1 large onion, finely chopped¼ to ½ a large chilli – depends on how hot you like it½ tsp ground dried ginger (fresh ginger would have been hard to come by in Georgian times)½ tsp curry powder – ready-mixed is fine. Although the blend varies, the staples are ground coriander seed and cumin, and milder versions are more authentic – the Georgian palate was subtler than nowadays.½ tsp turmericSalt and ground black pepper to tasteA little cream (optional)Finely chop the chicken – it will not be blended at the end, so keep the pieces small. I fried them lightly in a little oil, as we no longer have the chicken skin to add fat to the mix, then added the water and boiled for ten minutes until cooked through. Add half the chopped onion, the chilli and spices, cover and leave to simmer for half an hour. In a separate pan, fry the remaining onion with a little oil until golden at the edges, then add to the soup. Most Georgian recipes would likely have been finished off with a little cream, although it is not specified here. If using cream, take the soup off the heat before adding it, and serve immediately. I left it out of mine, and it was excellent without – up to you.

I was very pleasantly surprised by this recipe – despite the

relatively few ingredients, it is intensely flavoured and delicious, and the

chicken, the onion and the spices all really shine. This does make sense, given

that this recipe served in England

would have been to show off the unusual Indian flavours. It tastes unusual

mostly because soup nowadays has more body – potatoes, or lentils or rice – but

this would have been served a la

francaise with lots of other dishes at the same time – it was an appetiser,

and not expected to be filling. I do recommend it, if you like both soup and

curry – it’s a very fresh taste, and would be lovely with a bit of naan bread.

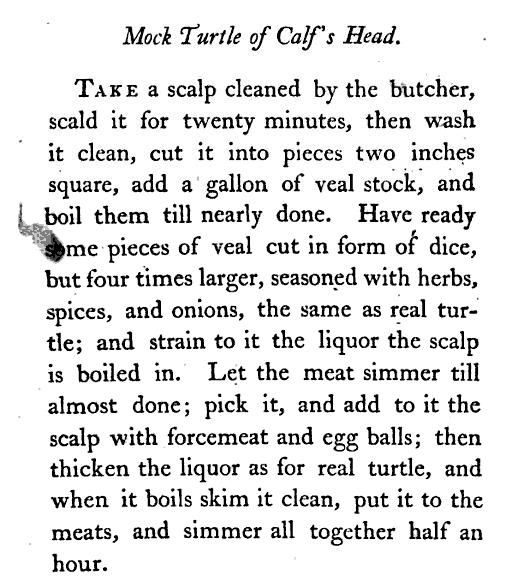

I can’t really talk about decadent Georgian dishes –

especially soup – without mentioning the ultimate prestige meal – the turtle

dinner. Turtle is a rich, fatty, and above all expensive meat that wealthy

households could make the basis of a whole meal, with the most ubiquitous dish

being turtle soup. Now, most people couldn’t afford to buy a turtle from the Americas – so

‘mock turtle’ soup recipes began to circulate, and now these are arguably more

famous than the original. Here’s a contemporary recipe from 'The Art of Cookery Made Easy and Refined' by John Mollard (1802), using the usual

substitute – a calf’s head:

Indeed. Nowadays,

recipes are a little less gruesome, and generally made from oxtail, which

strikes me as a little dull – I’d go with the Malaga Tawney every time – and

maybe follow it up with something chocolatey. Georgian style, of course.

Chocolate wasn’t a new flavour in Georgian times, exactly –

but it wasn’t yet eaten as a dessert, either. Instead, it was grated into water

or wine, which sounds very strange to modern ears. Naturally, I had to give it

a go.

Heat your red wine in a saucepan – don’t let it boil, but until it steams a little. (I used a cheap Merlot, but really, the type of wine doesn’t matter too much.) Then, finely grate in some dark cooking chocolate – perhaps 25g per glass, plus sugar to taste – 2-3 teaspoons per person works – and some ground nutmeg for that traditional Georgian flavour. Stir until all ingredients are dissolved, then remove from the heat. Serve hot, so preferably try not to make it in the middle of a heatwave, like me. (I regret nothing.)

I was dubious about this one – apart from anything else, I

thought it might curdle. But the plain chocolate dissolved nicely as I stirred

it into the hot wine, and stayed dissolved when I took it off the heat. It

looked rather thick and bloody as I poured it into a wineglass (note to self –

remember this for next Halloween) but as soon as it was cool enough to take a

sip… Oh my. This is delicious. It’s

rich and fruity and decadent and just sweet enough to take the edge off –

absolutely lovely. Next time I hold a dinner, forget pudding – I’m serving this

instead. As soon as the weather cools, do yourselves a favour and try this. No

wonder the wealthy Georgians didn’t bother inventing chocolate bars – they had

this drink instead. Lucky, decadent people.

Cheers!

No comments:

Post a Comment